Welcome back. This series is a look at the Productivity Commission’s report “Better Urban Planning”. For now, we’re looking at the background to their proposals.

Part 1 looked at the state of New Zealand’s cities today. This part will look at how we plan our cities and some flaws in that system.

How does our system work?

New Zealand’s planning system is complex, especially for such a small country. Planning is split among three major laws, with little connection with each other.

-

Regulation of land use and coastal issues is in the Resource Management Act

-

Transportation planning is governed by the Land Transport Management Act

-

Budgeting, services, and infrastructure are the domain of the Local Government Act. This also gives councils some regulatory powers, for example over parking and air pollution.

And that’s just the major ones. There’s also separate laws governing public reserves and conservation, local body rates (property taxes), and construction. There’s also numerous special provisions for Auckland, as our largest city, and Canterbury, with a complex rebuilding effort after the 2011 earthquake.

The RMA is the king of these laws, though. The law is a very general framework. It provides a lot of specifics about the process of planning, rule-making, and the process for getting resource consents. But it says very little about the actual content of those plans other than some very high-level principles of “sustainable management”. It’s left up to local government - and the courts - to make the substantive decisions.

It was designed as a reaction to the previous system. The old Town and Country Planning Act was quite similar to the systems used in North America - decentralised, and prescriptive. The RMA was supposed to do away with the idea of government imposing solutions, and instead produce “tightly targeted controls that have minimum side effects” (p100). As long as applicants could show that they had “avoided, remedied, or mitigated” harms to the environment, it would be left up to the market to decide how our cities should evolve. Planning would only make sure that the “effects” of activities did not harm nature or other people - it would not decide what should happen.

But that didn’t happen in practice. Most councils kept plans that were similar to the “District Schemes” of the old law, with detailed lists of activities allowed in particular locations. Most plans kept the style of zoning developed in the United States. This meant that the key tool of planning was that different activities were restricted to different areas, rather than looking at what effect those activities actually had.

Town and Country

Oddly, the RMA also doesn’t actually seem to have anything to say about cities. It only mentions “towns” in the name of the Town and Country Planning Act, the planning law we had until 1991. “City” only comes up when saying which cities you have to run public notices in the newspaper. “Urban” didn’t appear at all until 2009, and even then it only applies to a very specific issue - how much detail a local council needs to go to in order to have rules about protecting trees1.

This is more than just symbolic. “Key features of the RMA cited as restricting its usefulness in urban areas include its largely reactive character, its limited scope to deal with cumulative effects, and its focus on managing negative impacts rather than planning for positive effects” (p91).

Decentralisation and the “Democratic Deficit”

We do not have a federal system, but we still have three tiers of government - central, regional, and territorial. Central government also has several agencies involved - the Department of Conservation, the New Zealand Transport Agency, the Ministry for the Environment, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Internal Affairs, and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. But most of the work is done by the bottom two tiers of government: regional and territorial councils.

This is a problem, because local government is not particularly representative. While it’s nominally democratic, it has some real issues with who it represents. New Zealand is big on “consultation” processes, where members of the public have their say on the operations of government. But these consultations tend not to include everyone.

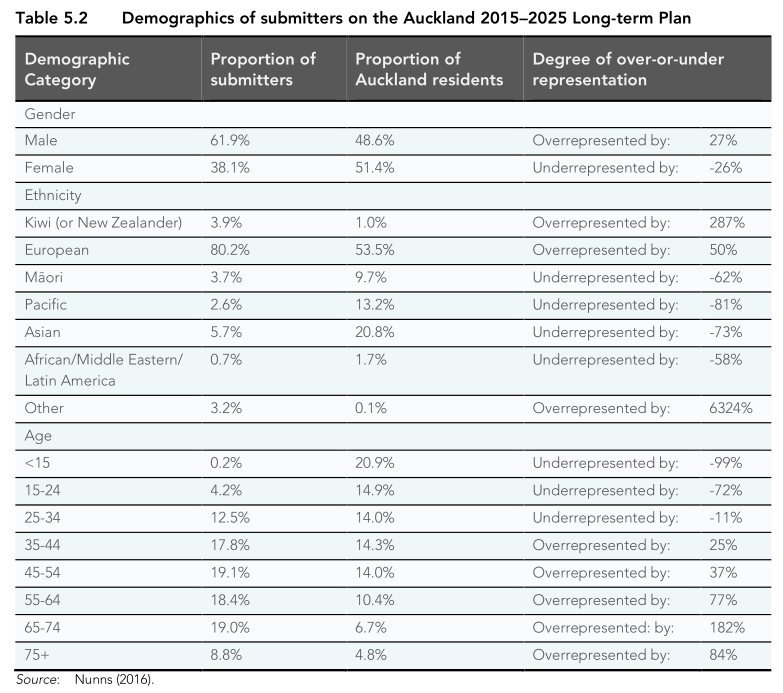

One example is drawn from Auckland Council’s Peter Nunns, writing at TransportBlog: the demographics of people who submitted on the council’s “long term plan”, effectively the budget.

While we have elaborate consultation processes, they still tend to hear a very narrow range of views. It’s only a small section of society that shows up, and the interests of everyone else tend to be discounted.

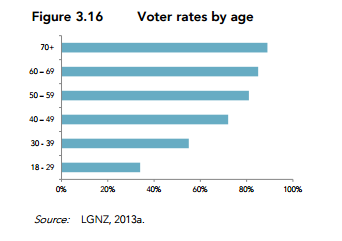

The voters for local government are not very representative either, and here we come to an issue where I think the Commission has got it very wrong. They take it as an article of faith that governments that represent a particular geographic area are somehow “closer” to the people (e.g. on p52). But there’s a huge bias in this - it gives the loudest voice to people who are most closely associated with that particular area. Homeowners and landlords rather than renters, the stationary rather than the mobile, the old rather than the young, people with several generations of ancestors here rather than immigrants2.

Here’s the split of voters by age. There’s a massive different in turnout between young and old.

This has very real effects. Local government isn’t good at taking account of national issues, but it’s bigger than that. All of these factors are proxies for one major thing: local councils mostly care about people who currently own houses, have lived in them for a long time, and intend to keep living in them. It also overrepresents people who are most concerned about paying rates, as compared to the value we might get from spending them. “Existing homeowners also have a disproportionate influence in the policy and political processes, and tend to be the dominant voters in local body elections” (p111). This is also the case in national elections, but it’s less extreme.

Low turnout and skewed demographics are not a problem with the voters themselves. They’re a sign that candidates are out of touch and not presenting real options. The Commission doesn’t address this, and that’s a shame. But nonetheless, some of their proposals have the side-effect of reducing the disproportionate power of some groups, as we’ll see in part 3.

Outcomes

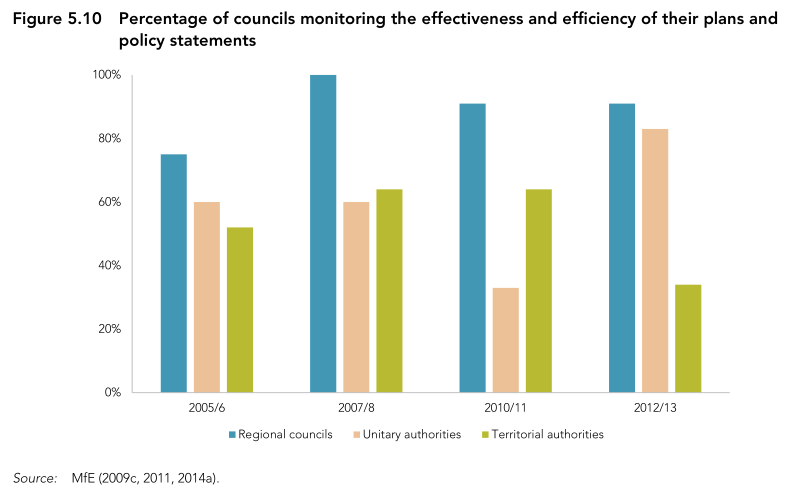

All of this would still be less concerning if our planning system was at least doing a good job. But there’s major problems. First is that councils often don’t even have much idea whether their plans are working, because they don’t check! Most territorial authorities do not monitor what effects their plans actually have.

There are some things we do well. We have some of the best air quality in the world (p128), and good access to “green space” (p143).

But other things are less rosy. Our freshwater is badly polluted (p133) and in some cases getting worse. Our greenhouse gas emissions have rised rapidly since 1990 and have only just begun a very slight decline. We produce more trash (p147) and have less effective wastewater treatment (p148) than most other OECD countries.

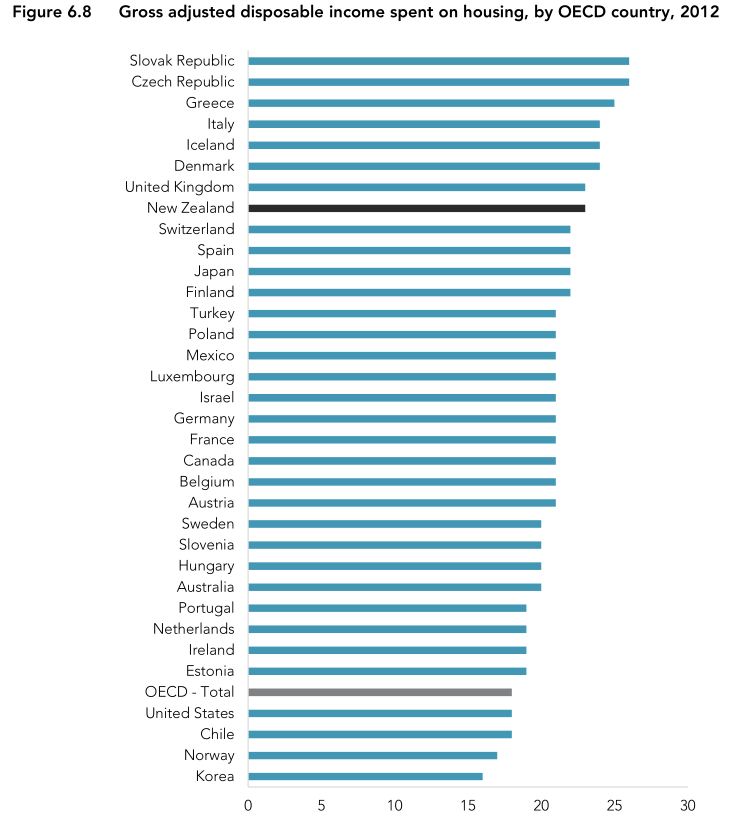

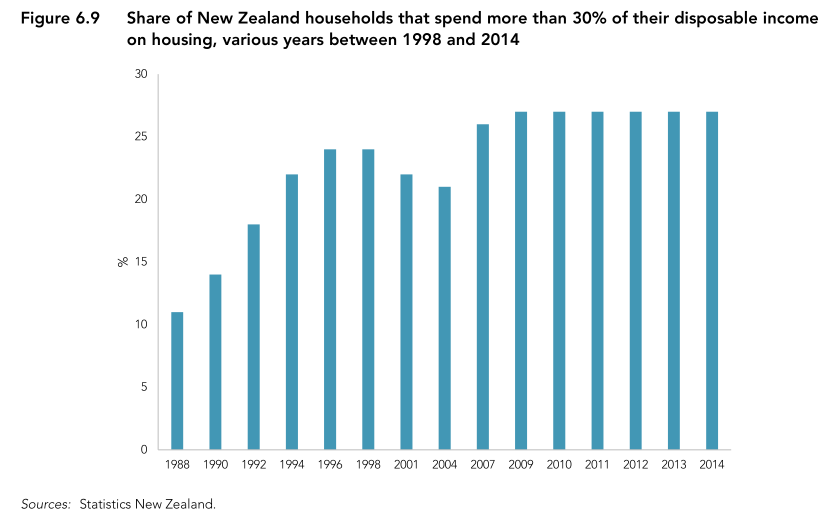

And that’s just the environment, supposedly the main priority of the RMA. When it comes to one of our most fundamental jobs, we’re doing appallingly. Our housing is more expensive and hard to find than most other countries, even in a time when many countries have housing problems.

…and it’s getting worse.

10% of Aucklanders are in “crowded” housing. 6% are in “severely crowded” housing3 (p140).

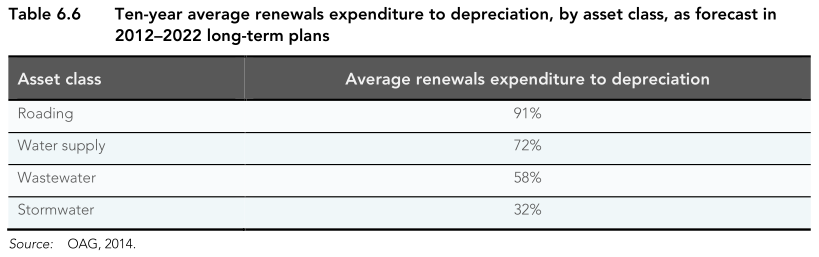

What’s more, we’re not even keeping up what we’ve already built. We’re mostly renewing our roads, but water, stormwater, and wastewater infrastructure is coming to the end of its life, and not being renewed.

Not all of this is the fault of planning. Despite what Bill English might think, planners do not have unlimited power and nor is city planning able to fix every problem. But it is the cause of at least some issues.

So what next, wise guy?

That’s enough for today. In Part 3 we’ll go high-concept and look at what planning is supposed to achieve, what the commission wants to do, and some exclusive hot takes of my own.

Notes

1. In urban areas councils must define specific trees or groups of trees to protect. Otherwise they can make rules that apply to a class of trees generally, for example any tree over a certain height.

2. Although that doesn’t translate into much consideration for Māori, especially urban Māori who no longer live in their traditional lands.

3. This is based on a Canadian standard. The target is that people over 18 should only share a bedroom if they are a married or de facto couple. Children 5-17 should only share a room if they are the same sex. Children younger than 5 can share rooms with the opposite sex as well. “Severely crowded” means that you live in a house where you are at least two bedrooms short of meeting this standard.