It’s been several months since I wrote Part 2 of this series, looking at the Productivity Commission’s report on urban planning. Back then, it was a draft, however, they’ve just released the final report. The final report is updated from the draft in many ways, but keeps the same broad thrusts. So, now is an excellent time to pick up where we left off.

We’ve got this far without completely going back to basics. But the Commission did, and so we will now too. All of this is in Chapter 3 of the final report.

So, it’s time to ask a question I often get asked when making chit-chat at parties1: what is urban planning, and why do we do it?

What is urban planning, and why do we do it?

There are as many answers to this as there are planners, although they tend to boil down to some common factors. Urban planning is the design of cities, the arrangement and connection of their components, and the control and provision of what happens within them.

Planning’s ends are to make people’s lives better. We plan cities to protect the environment, we plan cities to keep ourselves safe, we plan cities to make ourselves prosperous, we plan cities to be good place to live in, we plan cities so that people can get in and out of them and around within them. If we’re really doing well, we might even plan cities to be beautiful.

image: Luke Zeme, CC-BY-NC-SA, Flickr

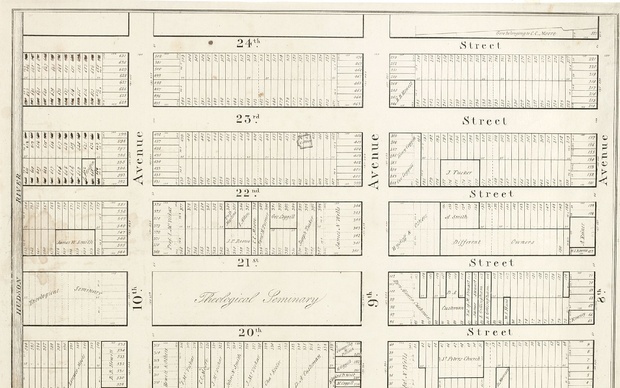

Planning is almost as old as towns themselves. It started with planning the physical layout of towns2, in terms of streets and squares and public buildings. In the thousands of years since it started, planning has expanded its scope to cover land use, transport, infrastructure, economic development, community development, public services, the protection of nature, and a whole host of other things, depending on where you draw the boundary of what counts as planning.

Planning’s means are many, but in general, they come from two places: the power of the government to regulate, and the power of the government to spend money. Planning is, by and large, a government endeavour. Planners design and enforce rules for the private sector, and for other parts of the government. Planners also inform decisions about what the government does in public places like streets and parks, the projects it builds, and the services it provides.

Does any of that even vaguely work?

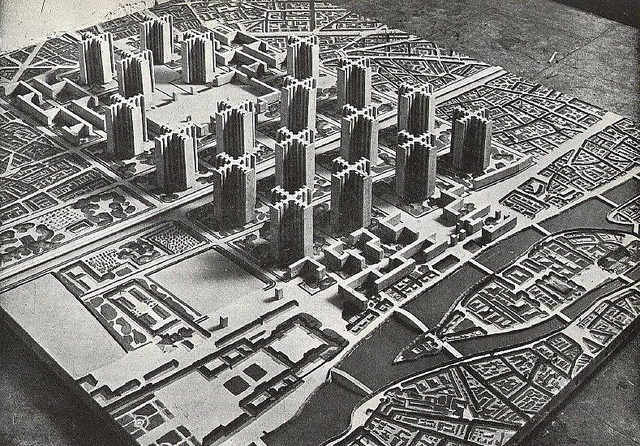

It’s possible planning may have bitten off more than it can chew. By the 1960s, planning was routinely failing to deliver any of its stated goals, and a backlash started. This was driven by some good reasons, I might add. Laypeople began to rise up against plans for inner-city motorways and massive, soulless, Corbusian housing blocks.

image: New York University

Rapidly, planners began to internalise the backlash and planning spent decades disowning any claim of expertise about cities. Public participation became the ideal of the day, and at the extreme, “tools and processes introduced to ensure popular participation ended up reducing the planner’s role to that of umpire or schoolyard monitor” (from previous link).

Skepticism of the very idea of city planning is still alive and well today. Again, this is understandable - city planning has often been done badly. But just as bad architecture does not mean architecture is not needed, bad planning means we need good planning, not no planning.

image: New York Historical Society

It’s in this background that the Productivity Commission starts to justify planning, and decide what the limits on it should be. It’s heavily based in economic theory - as you’d expect, given the rationale of the organisation. It also focuses fairly heavily on one of the two major tools of planners - regulation. This again is what you would expect from an organisation of its political bent.

So what does the Productivity Commission see as the role of planning?

There are numerous purely economic reasons for a government role in city planning (p48). Sewage treatment and parks and streetlamps are all public goods, which need to be provided at public expense if they are going to happen at all. Negative externalities such as pollution or noise need intervention to avoid people dumping the costs of their activities on others. Natural monopolies like piped water or roads need to be provided or at least controlled by the government. Some activities like railways and airports could theoretically be delivered privately, but are probably just too big for any private-sector organisation in New Zealand to attempt without government support.

image: Auckland Transport

… and that’s about it. The Productivity Commission has a very strong right-wing political leaning, since that is after all the reason it was set up. They see a role for government - especially local government - that is as small as possible. “Roads, rates, and rubbish”. So thus, they see the role of government-run urban planning as also being as small as possible.

For those on the left, which includes me, government has a bigger role to play to improve people’s lives. But in large part I still agree with a lot of what the Productivity Commission is proposing around reducing regulations, being less prescriptive, and going for “spontaneous order” instead of “made order”.

The left has for decades been a fan of “too-clever-by-half” regulations to achieve social goals. This attitude has flowed into planning, too. Instead of just building State houses for people, we’ll make complex regulations to try to encourage developers build affordable houses. Instead of spending money to plant street trees, we make people have landscaped front yards to soften the look of our ugly streets.

It hasn’t worked, and even when it does work no-one notices. Regulate less, and spend more.

How to plan

Once we know what planning is trying to achieve, we need to figure out how to achieve it. So the commission looks at the major styles of planning (p55). They have almost entirely relied on the views of Italian theorist Stefano Moroni, who has some fairly strong stances. There’s a number of distinctions that can be made, and in each case the Commission has a pretty obvious preference.

“Made order” or “spontaneous order”?

Should planning set out to deliver a specific goal, or should planning be about setting the right rules? The commission strongly favours the second view, that once we establish rules that meet our theories, we should stand back and accept whatever results as being the best outcome.

Prescriptive or performance-based?

Should planning specify rules about what can and cannot be done? Or should it specify the result of the actions we take? Older New Zealand plans tended to be prescriptive, which is no longer in favour. Modern laws like the Building Code and RMA tend to be based around the idea of “performance standards”. This has the advantage of allowing creative solutions that the plan-makers didn’t think of, but the disadvantage of being less predictable about what will be approved and what will not. The commission favours the modern preference for performance-based regulations.

Bottom-up or top-down?

Should planning be bottom up or top down? Top down planning is fairly obvious - some bureaucrats in an office in Wellington give orders, and everyone else follows them. Bottom up planning is trickier to define. Generally, it involves lower, more local levels of government, and more public participation and consultation. However, when consultation tends to be dominated by a narrow section of the community, this “bottom-up” state may not be achieved in practice.

What I think

Generally, I think for each of these divisions, there’s a role for both. And for each of these decisions, all of the first options go well together, and all of the second options go well together.

We need top-down planning, which is best suited to planning via regulation, creating “spontaneous order” rules and judging the outcomes of performance-based codes.

But we also need bottom-up planning, which is better suited to delivering specific plans and prescribing outcomes. Except for mega-projects that are beyond the capacity of local government, it’s also the best suited to levy rates and spend money on services. But we still need to decide just who is going to do what.

So what now?

Well, today we’ve covered the theory. We still need to put theory into practice, though. In Part 4, we’ll look at what is to be done.

Notes

-

In Wellington, someone will ask “so what do you do?”, in Auckland, someone will talk about house prices or traffic: regardless, the topic of urban planning is coming up. ↩

-

Curiously, planning seems to have backed away from this in recent generations. This is probably a bad thing. ↩