Planning is a surprisingly hot issue at the moment. From the housing crisis to the Unitary Plan, water quality to public transport, everyone suddenly seems to care about how our cities function. The government is certainly taking an interest, too. So much so that it has three separate reviews of planning and RMA issues going on.

Perhaps the most prominent of them is being run by the Productivity Commission. After rounds of consultation and submissions, last Friday they released the draft report, “Better Urban Planning”.

It’s an interesting report in a number of ways. It’s completely ground up, reviewing the history and rationale of city planning, and the economic and social trends of New Zealand’s cities. The terms of reference are to “review New Zealand’s urban planning system and to identify, from first principles, the most appropriate system for allocating land use through this system to support desirable social, economic, environmental and cultural outcomes” - a pretty big job!

The report proposes some fairly big changes to the way we plan. I’ve been reading through, and there’s quite a lot that’s interesting. There’s no new research, but there’s a lot people may not have heard of, and some interesting syntheses of existing information. However, the report is north of 400 pages, so I’ve summed up some of the best parts here. Even then, there’s a lot to cover, so I’ve split this up into several parts. This is part 1.

Where are we now?

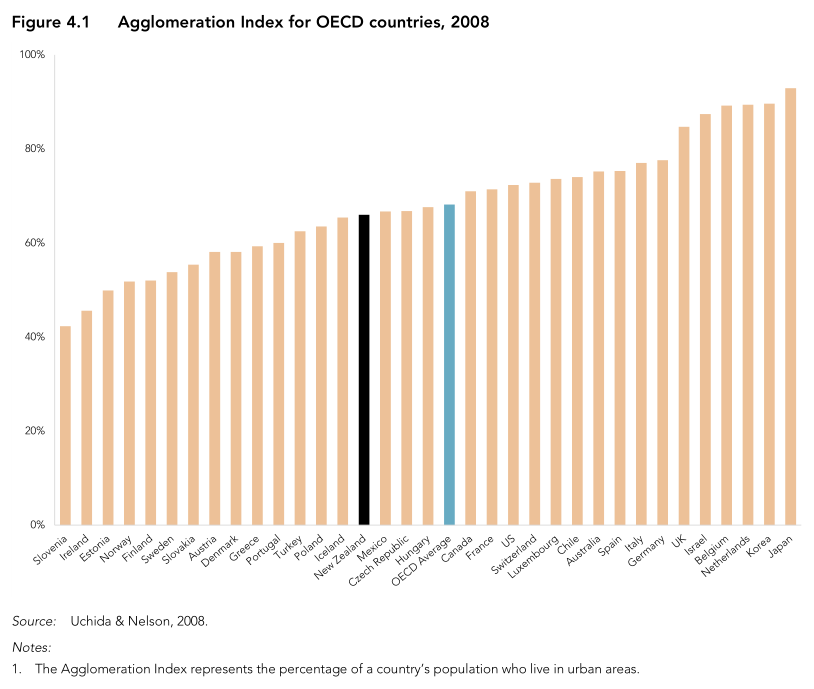

New Zealand is a highly urbanised country, and like the rest of the world, is only getting more urbanised. But in part this depends how we define “urban”. According to our own definition, 86% of New Zealanders live in urban areas. But if we use the standard definitions for other countries, we’re actually less urban than the average OECD country.

That said, more than 70% of New Zealanders live in cities larger than 50,000 people. One third live in Auckland (p20).

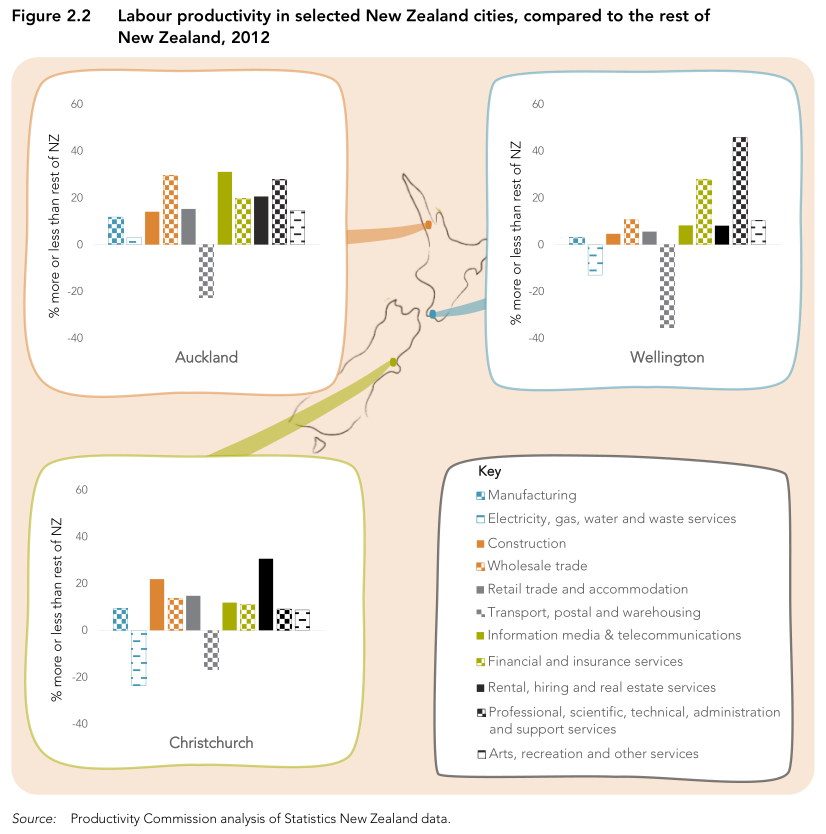

Why is this so? There are huge benefits to cities, called agglomeration benefits. Proximity and population lower the cost of doing business. A larger population means a bigger pool of jobs to choose from, and expands the range of goods and services and other amenities you can enjoy. Economies of scale mean that providing public and private services is cheaper when the fixed costs can be spread wider. People can change jobs more easily, and couples can more easily find jobs for both partners (p22).

But agglomeration is not all positive. There are costs to size, such as extra air and water pollution, traffic congestion, and higher prices for some goods, particularly housing. Part of the goal of city planning is to reduce the downsides of scale while increasing the benefits.

The costs and benefits of cities can be subjective, and depend on people’s individual preferences. Different people will make different tradeoffs. There are some stark illustrations of this. In general, more people move from Wellington, Hamilton and Christchurch to Auckland than go the opposite way. Yet Auckland in turn loses more migrants to the small towns and cities in the rest of New Zealand than move to the big smoke (p69).

But Auckland continues to boom. Auckland’s population is younger than the rest of the country, and has a higher birth rate. “Auckland is unique in that it is larger, younger, denser, faster growing and more ethnically diverse than most other [NZ] cities” (p64).

It’s also the destination for the bulk of international migrants, which is also a large factor in Auckland’s growth. “Over 42% of Auckland’s growth since 1996 is due to migration, compared with 15% for the rest of New Zealand” (p70).

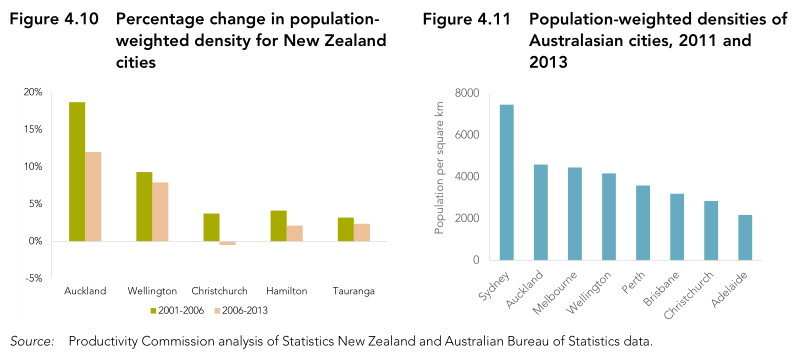

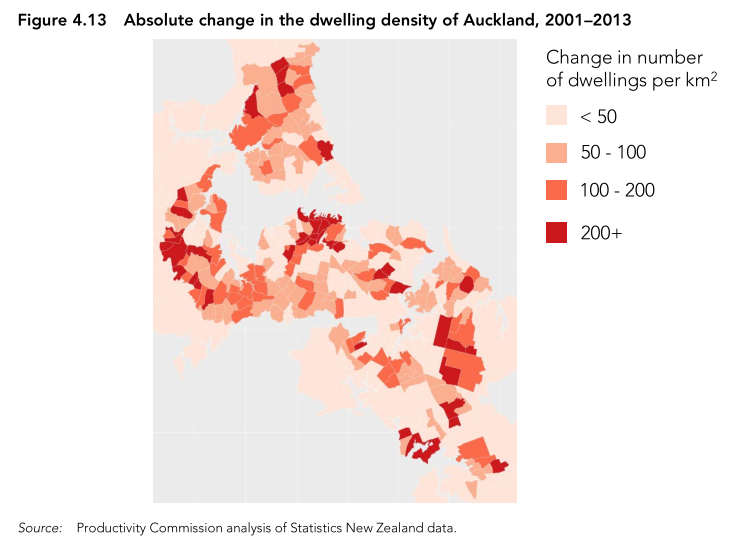

In addition to growing more populous, our main cities are also getting denser - that is, they’re not growing out as fast as they’re adding new residents. The neighbourhood the average Aucklander lived in got 33% more dense from 2001 to 2013 . Four of our five largest cities (not Christchurch) got denser during this time. New Zealand’s cities are among the densest in Australasia, but not very dense by world standards (p74).

So does that mean we’ve been getting intensification? Councils often have a policy to encourage growth to happen by increasing the density of central areas, and increasing density across the city seems like it would mean that they are succeeding.

But actually, it hasn’t really been that way. Wellington had the majority of its growth in the central city, by transforming industrial and commercial space to residential. The other cities all got denser in a strange way. The new suburbs they built were simply much denser than existing urban areas. This has meant some weird patterns, particularly in Auckland, where outer suburbs are much more dense than inner suburbs. More than 70% of Auckland’s new dwellings were more than 10km away from the city centre (p75).

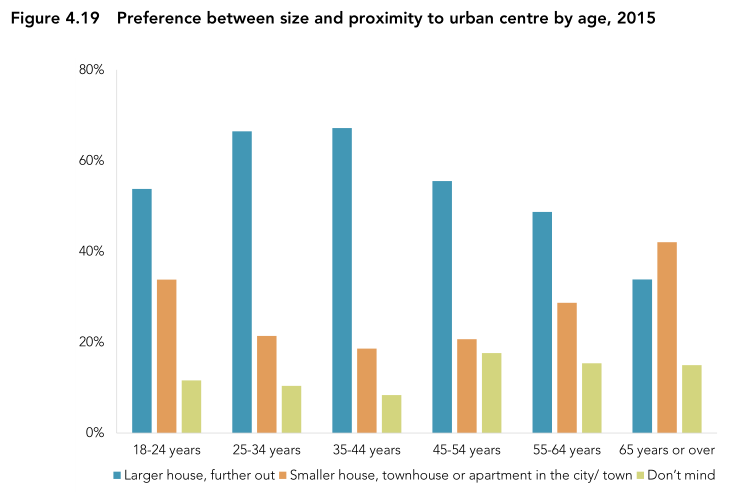

New Zealanders also tend not to be too keen on intensification. The majority prefer a larger standalone house, even if that means living farther away from town. This is particularly strong among the middle-aged. There is, however, one very interesting exception. People over 65 are the only group who are more likely to prefer a smaller house or apartment closer to the city (p80).

Some New Zealand towns and cities, particularly the smallest, aren’t growing at all, or are even shrinking. They generally have ambitious plans to reverse those declines, and generally, they haven’t worked. A few towns, however, accept that they are shrinking, and are planning with this in mind. Rangitikei District Council (which covers Bulls, Marton, and Taihape), for example, is aiming to reduce the size of its water and road networks as the demand for them reduces (p86).

Different places have different issues providing for residents. There’s also environmental issues, social, and economic factors to consider, not to mention the politics of it all.

That’s probably enough for today. In part 2 of this series, we’ll look at how New Zealand’s urban planning system deals with these challenges today.