This article has also been cross-posted at Greater Auckland and you can comment there.

New Zealanders are probably most familiar with the Resource Management Act (or “RMA” for short) as being about protecting the environment: when it’s discussed by politicians, it’s almost always either being decried as having environmental protections that are too onerous and stand in the way of progress, or alternatively being supported as the main defence of environmental health.

This perception isn’t wrong by any means - much of the RMA is about these protections of the environment in an ecological sense. Some aspects - fishing, minerals, conservation land - are handled separately, but most of the state’s regulations that aim to protect clean air, clean water, protecting the coastline, wetlands, native vegetation and wildlife habitats, and so on, come under the RMA.

But the RMA does far more than just what we normally think of as the “environment”, and this fact is probably less widely known. The RMA is also the main city and regional planning law, and planning traditionally covers social and economic matters as well as the purely ecological. This is done in an intriguing way: by creating a law focussed squarely on the “environment”, but then defining “environment” to include all manner of things outside the traditional understanding of that word. The RMA then defines its purpose as being to avoid “adverse effects” on “the environment”.

In the RMA, the definition of “environment” is broad, and includes:

- “people and communities”

- “social, economic, aesthetic, and cultural conditions”, and the big one:

- “amenity values”.

Keep that term “amenity values” in mind.

Ample Parking Day Or Night

New Zealand has a built form most similar to other Anglophone New World countries: Australia, Canada, and the United States of America. It’s long had a series of planning rules similar to those found in those countries: a focus on limiting density, spacing buildings out from the street and from neighbouring buildings, limiting the height of buildings and the shadows they cast, and almost universally, requiring that there be enough car parking provided on-site for the maximum number of visitors and residents the building is ever likely to have, assuming they all arrive alone in a self-driven car.

The other three countries, like New Zealand before the RMA, don’t require any sort of philosophical justification for this: it’s just there because policymakers and/or the voting public think it’s a desirable thing to achieve.

In New Zealand, however, the RMA requires any such regulation to be justified in terms of the “environment”. That idea of “amenity values” as being an environmental value is used to justify a large fraction of the planning rules that New Zealand has, including parking requirements.

This seems to be somewhat contradictory. Councils generally also have policies that are supposed to discourage driving, or at least promote alternatives to it, for reasons that are environmental in the normal sense: avoiding the air pollution and carbon emissions caused by petrol and diesel engines, the water pollution caused by oil and brake dust runoff, the environmental impacts of oil drilling to fuel the vehicles, and so on. Not to mention the other costs of driving that are not environmental in the traditional sense, but are in the RMA’s definition: the delays caused by traffic congestion, the deaths and injuries caused by driving, and the sheer financial costs to households of owning and running cars.

But there’s more to parking that just arguing about whether it’s a good “amenity”, or bad environmentally. There’s also the question of paying for it.

The High Cost Of Free Parking

Most carparking spaces in New Zealand, on-street or off-street, are provided at no direct charge to the person using it. That doesn’t make them “free” in reality: carparks all sit on land, which isn’t free, and most of them cost money to build, which can be a serious expense in multi-storey structures.

Carparks at people’s homes are bundled into the purchase price or rent. Carparks at shops are bundled into the costs of the goods and services they sell. Carparks at workplaces are effectively a fringe benefit of working there, and so come out of the wages of workers. This is less of an issue if you’re paying one way or another, but this system has two natural consequences:

- You pay for parking whether you personally use it or not, which is a strong incentive to drive even if you otherwise wouldn’t have.

- You pay for parking even if it never gets used at all by anyone, which is purely wasteful.

This is an issue that’s been known for some time. The title of this article refers to the title of the book that is probably the best-known critique of free parking, by Donald Shoup, professor of urban planning at UCLA. You can see this interview with him conducted by Vox.

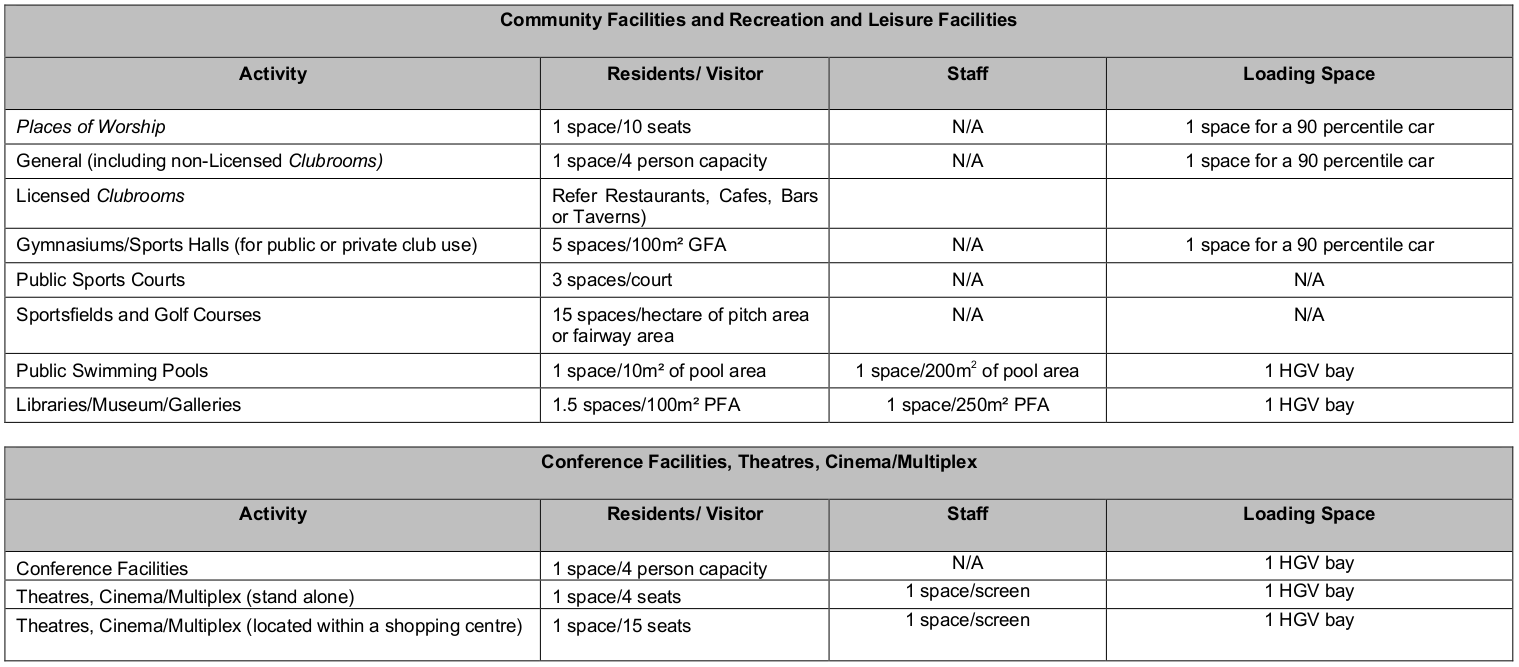

Our planning system doesn’t explicitly require that parking be free. It does, however, require a certain amount of it. Typically, for big developments, you hire a traffic engineer to do traffic studies and produce a report justifying how much parking you need. For small and medium-sized developments, you normally just literally look the numbers up in a large, incredibly detailed table in the District Plan.

One small part of the Tauranga City Council table of parking minimums

One small part of the Tauranga City Council table of parking minimums

Fail to provide “enough” parking, and your development will be turned down, even if you’re in a place with good alternatives like cycling or public transport, or even if there is simply ample alternative parking.

In general, these numbers are just copied from other nearby councils or come from professional traffic engineering guides. The original sources of the numbers is traffic studies: someone going out to an existing development with unrestricted parking, with a clipboard, at close to the busiest possible hour of the busiest day of the year, and counting how many cars are parked there. Then rounding up a bit. So the minimum amount of parking you must provide is slightly more than the maximum that might ever be used. Under these conditions, there’s pretty much no point ever charging for parking, since there’s never a shortage.

But Why Though

Why do we not just let developers decide how much parking to build, then live with the consequences of building too much or too little? Remember that this scheme is justified in terms of “amenity values”. When a development is proposed, there’s a benefit for visitors and residents in it to always being able to get a parking space, gratis. But that isn’t the theoretical reason we’re doing this. The “amenity” is to everyone else nearby. If our development doesn’t provide enough parking, people might park on the street (the horror!), and if enough people did this, all the on-street parking would be used up, and then people living in or visiting neighbouring homes and businesses wouldn’t be able to park on the street1.

So, the terrible “environmental” effect we’re avoiding is… people using on-street parking spaces. Which are only there in the first place to be parked in! In the worst case, some people might have to park a little farther away, or need to put in their own on-site parking, or the council might need to manage on-street parking by putting in time limits, meters, or a system of residential permits.

This imposes vast costs on new developments, which are passed on to their residents, customers, and employees, whether or not they drive. It’s particularly acute in higher-density developments. First, because higher density developments tend to be in places with better alternatives, like walking and public transport, so fewer people want to use the spaces in the first place. Second, if parking spaces need to be built in a basement or multi-storey structure, they can cost $30,000-$50,000 to build. In a day and age when the cost of housing is one of our biggest political and social issues, is this a smart policy?

Under the NZ planning system homes for cars are more important than homes for people

— Francis McRae (@FrankMcRae) September 5, 2018

Who Will Rid Me Of These Troublesome District Plan Requirements?

This is not a new issue. You can see in this video the current Associate Minister of Transport, Julie Anne Genter, then a professional transport planner, arguing against parking minimums nearly ten years ago. The Minister himself agrees. In opposition, both pushed during negotiations on RMA reform to abolish parking minimums. So why hasn’t it happened?

The RMA is a political football and hugely contentious. It’s been amended, on average, more than once per year since it was first enacted in 1991. But never have the core values been touched: the definition of “environment”, or the “matters of national importance” that are supposed to be central to decision-making. In part, it’s just been too hard for a coalition government to agree on lofty philosophical issues. The previous National government could never get its support partners ACT and the Māori Party to agree, and the current Labour government is likely to have similar problems with its support partners the Greens and New Zealand First. Amendments have tended to be either extremely ad-hoc about specific issues, or generic changes to procedures, hoping that councils will do the hard work.

Councils could do the hard work, in principle. The RMA does not require parking minimums, it merely allows them. Auckland and Wellington have both abolished parking minimums in their CBDs and in some suburban town centres. But even the most courageous councils tend to be more conservative than central government. With low voter turnout and small constituencies, councillors are more worried about criticism from a vocal minority who want to retain free parking than lofty but abstract ideas of economic efficiency or fairness. They’ve had decades to act, and haven’t.

Maybe someday we will get a more comprehensive reform of our planning system. I suspect it’s still many years away. But in the case of parking, I think there is an alternative to legislative reform that doesn’t rely on councils, and can happen far more quickly.

Setting The Standard

Councils adopt parking minimums through having rules in their district plans. Comply with the rules and you are fine. If you don’t provide enough parking, you need to apply for resource consent, which typically (though not always) will be declined. As seen above, this is a series of numerical tables, providing a standard which needs to be met, at which point you will be judged to have avoided an adverse effect on the environment.

The RMA provides that councils can set standards for the environment. It also provides that the central government can set a standard, if it’s seen as desirable for the standard to be uniform across the country. It can choose whether or not councils can provide a higher or lower standard. There is a process that has to be followed, with a series of public hearings and technical reports, but ultimately it’s up to the Minister for the Environment and Cabinet to decide what to enact.

This is done with an aptly named National Environmental Standard or “NES”. This is one of three main ways that the central government can issue directions to councils without legislative change. The others are:

-

National Policy Statements, which the previous National government created several of. The downside is that they don’t have direct effect: they are general policies that local councils are obliged to follow, but they are only obliged to follow their own interpretation of them.

-

National Planning Standards, which were only introduced last year and haven’t seen much use yet.

Any one could be a useful tool. I think the NES is the most apt, however. It has direct effect, and isn’t subject to being “interpreted” into nothing by councils. It’s also intended for crunchy, technical, numerical standards, which is what the parking system currently is.

What Would A National Environmental Standard On Parking Look Like?

An NES can set essentially any rules that a District Plan could. A NES could, in principle, reproduce parking requirements similar to current ones, but simply standardised across the country. Obviously, this would be a bad idea.

But it could instead provide that, in urban areas, the minimum amount of parking required is zero. Councils would be able to set a maximum amount of parking, but they would not be free to set the minimum at anything other than zero.

This may seem a little cute: using a method intended to set a standard in order to abolish the idea that there should be a standard. But it’s not without precedent. There is a NES on “telecommunications facilities” for example, which among many other things is intended as a measure to abolish council powers to restrict the siting of telecoms boxes on footpaths.

It’s also possible we might want to retain some standards on parking: requiring loading spaces for large developments, parking for bicycles (which Auckland Council does), and various geometric design standards for parking where developers do voluntarily choose to build it, for example2. We might also possibly want to keep parking requirements in rural areas, where significant amounts of on-street parking on 80 or 100km/h roads tends to be a safety issue, and there generally is little or no alternative to driving.

One way or another, though, a National Environmental Standard could be a quick, easy way of abolishing the blight of parking minimums wasting land in our cities, and reducing the cost of parking oversupply on residents and businesses.

Notes

-

This seems to be incoherent as well. Why are the occupants of existing buildings entitled to free on-street parking at public expense, but the newcomers aren’t? However, this seeming unfairness isn’t really relevant to the main point. ↩

-

You may be thinking of disability parking as well: this is already handled through the building code, which does not require that there be parking in the first place, but does require a certain proportion of any parking that is provided to be disabled spaces. ↩