The week before last I wrote about why parking minimums are bad policy, and how easy it might be to end them. The excellent urban activist group Greater Auckland reposted it, and there were some interesting points raised in the comments section.

Today, I wanted to look by comparison at Japan, a country with a radically different approach to parking. Japanese policy, like New Zealand’s, was not consciously designed in one go, and in part reflects an evolution over time. It has its own flaws, but does, however, represent a different philosophy that’s worth examining.

Background

Japan today is famously one of the world’s largest manufacturers of cars. In 2016 it exported $101 billion worth of them, 14% of the world’s total, and the second-most of any country behind Germany. Cars are Japan’s largest single export, and vehicles and vehicle parts as a whole account for roughly a quarter of the country’s foreign income.

It may seem surprising then, that the government’s and public’s attitude to actually using cars has long been less than completely enthusiastic. Indeed - this skepticism of wheeled vehicles predates the invention of cars. In the Edo era (1603-1868) the central government even banned wheeled carts from the streets of central Tokyo1. Japan relied chiefly on water-borne transportation: Tokyo and Osaka in particular were built around large networks of canals.

Cars were introduced to Japan at the same time as in Western countries, in the last decade of the 19th century, but at first only became popular among the upper class minority who could afford them. Japan, then as now2 had no oil reserves worth speaking of, so running a car was even more expensive than in the West. Oil, parts, and cars themselves all needed to be imported. Pre-war Japan was also poorer than the West, without the sizeable middle class of countries like the United States or Britain.

Japanese cities, even more so than New World or even European cities, also had and continue to have little space for use by cars. By the end of World War II, while there were wealthy people living on traditional samurai-era estates, and some attempts to build “garden city” suburbs on the English model, the majority of Japan’s urban population still lived and worked in shitamachi3 areas: dense mixed-use neighbourhoods of low-cost and fire-prone wooden shacks, with most streets being too narrow for cars to even drive down, let alone have space to store them.

A relatively wide Yokohama main street in the early 20th century. Photo: unknown author

A relatively wide Yokohama main street in the early 20th century. Photo: unknown author

So cars did not become popular at first. Despite that, as in the West, successive governments have attempted since around the 1920s to remake Japan’s cities to be more motoring-friendly. Most of the big city canals were filled in for wide arterial roads. Sometimes the opportunity was used to widen roads after fires, and deliberate demolition allowed expansion. But these were solely big schemes for main roads. Most city streets remain roughly as narrow as they had been during the age of the samurai: the only big change is that they now are paved. Indeed, new streets in greenfield subdivisions tend to be similarly narrow, although always at least wide enough to drive down.

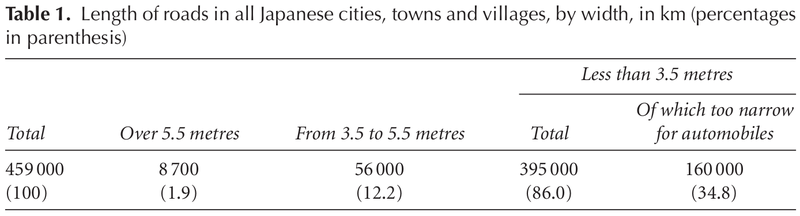

More than a third of Japan’s streets are too narrow even to drive down, and 86% are narrow enough that stopping a car would block all traffic. 2007 figures. Source: Sorenson, Okata, and Fujii, who in turn get this information from the Japanese Statistics Bureau.

More than a third of Japan’s streets are too narrow even to drive down, and 86% are narrow enough that stopping a car would block all traffic. 2007 figures. Source: Sorenson, Okata, and Fujii, who in turn get this information from the Japanese Statistics Bureau.

Doraibu

By the 1950s, Japan was experiencing its famous post-war “economic miracle”. Standards of living rapidly increased off the back of an astonishing industrial boom. Japanese goods like cameras and electronics quickly began to rival the West, and the country became a major exporter. The country’s car manufacturers were part of this as well, and began to sell cars overseas and to the domestic public in ever-increasing numbers.

But this boom in the 1950s and 60s was starting decades later than it had in the New World, or even in some wealthier European countries. America in particular, closely followed by Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, had used the car to allow its cities to spread rapidly into the countryside, rapidly building new suburban areas accessible only by car. Japan, in contrast with the New World, and more like Europe, was selling cars to an existing urban population who already had trains, trams, bikes, and feet to get around. Doraibu, a loanword from the English “drive”, was coined in the 1960s, but it meant something different, more akin to “to go for a drive”. It was a leisure activity, allowing Japanese to visit their countryside and natural areas. It was not a serious way of getting around town.

Once a significant fraction of the population started to buy cars, dealing with the sheer volume of cars quickly became a burden. This period in the 1950s and 1960s in the West would see, for example, the Traffic in Towns report in the UK, the Interstate Highway System in the US, and even the Master Transportation Plan in Auckland.

Japan followed suit, founding the Japan Public Highway Corporation in 1956, and opening the first section of expressway in 1963. There were some major differences, however. While the expressways were publicly funded through debt, the intention was for the system to pay for itself4. Fairly hefty tolls were present on all expressways from the start5. There was also less demolition in urban areas. Expressways were chiefly built elevated above wider surface streets, or above the remaining canals. Lastly, they were never intended to handle the volume of traffic that would be required if cars were the primary way of moving around town. The main urban areas were massively expanding their subways during this period, which meant that train travel remained more convenient than driving, as well as cheaper.

As well as moving cars, storing them when not in use quickly became a problem, as they clogged up the little available space on the streets. Internationally, the best “solution” for the parking problem was seen to be parking minimums, which were all-but-universal in English-speaking countries by the mid-1960s6. Japan’s cities adopted parking minimums as well, although at far lower rates7 than those found in the suburbs of the US and even than other dense cities in Asia, and with sweeping exemptions for smaller buildings.

At about 4 metres wide, this shopping street in the suburbs of Tokyo has a typical width for urban Japanese streets. There’s just no room to park on a street like this. Photo: author, CC-BY-SA.

At about 4 metres wide, this shopping street in the suburbs of Tokyo has a typical width for urban Japanese streets. There’s just no room to park on a street like this. Photo: author, CC-BY-SA.

Shako Shōmeisho

In 19638, however, Japan made a major departure from other countries. If you lived in a city, leaving your car parked on-street overnight was made illegal, regardless of how wide the street was, whether there was room, or whether on-street parking was allowed during the day. This is an approach that had been tried elsewhere, for example in New York, but had been long abandoned anywhere else. It was less radical, perhaps, in Japan: car ownership was still relatively low, a large fraction of streets were too narrow to park a car on regardless, and the people of Japan have a (possibly overstated) reputation for being law-abiding.

As a counterpart, to avoid violation of the rule, another policy was adopted at around the same time. It is almost unique to Japan, although a few other limited trials have been made in other countries. In order to register a car, you now needed to provide proof to the local police that you had somewhere to park it. If you had a garage at your home, the police would come to inspect it: the other main option was leasing a parking space from a private off-street parking lot in the neighbourhood around your home, and you could provide a copy of the lease agreement as proof. Only once this was done and you had your shako shōmeisho (literally, “garage certificate”) would you be allowed to take possession of the car.

This immediately kick-started a market in private residential parking, even in suburban areas. Particularly in more mixed-use areas, they also doubled as casual pay-by-the-hour parking for visitors and commuters. This was not entirely without cost, as gardens, vacant lots, and other privately-owned open spaces were rapidly converted into profit-making parking lots. But it did mean a network of commercial parking spaces existed within short reach of most city destinations, freeing smaller businesses and apartment building developers from any feeling that they might need to offer their own, on-site parking.

Coin Parking in Yokohama. Japanese neighbourhoods are peppered with small, standalone commercial parking areas, while many homes and most small businesses do not offer on-site parking of their own. Photo: Japanese Wikipedia user 亜利紗

Coin Parking in Yokohama. Japanese neighbourhoods are peppered with small, standalone commercial parking areas, while many homes and most small businesses do not offer on-site parking of their own. Photo: Japanese Wikipedia user 亜利紗

A Model of Market Parking

Japan today has car ownership rates similar to western Europe, so there certainly does need to be plenty of parking for them. The three distinct features: low parking minimums with wide exemptions, the proof-of-parking system, and a lack of on-street parking, produce what Paul Barter, writing for the Asian Development Bank, describes as a “remarkably market-oriented parking system with ubiquitous commercial market-priced parking”.

The good

That resulting system of standalone commercial parking lots seems to probably be the most efficient way of providing parking. Spaces are multipurpose, and shared across an entire neighbourhood, so there is not the waste of duplicate parking spaces at neighbouring businesses. You can also park just once, if you’re visiting multiple places in the same area.

The shared parking model also frees most small and medium-sized businesses from needing to decide on how much parking to provide. You can simply choose to outsource the decision: you provide no parking of your own, but your business is still accessible to customers who arrive by car.

Parking is also flexible in both the short and long term. Households can decrease the number of cars they own without needing to have garage space that will go unnused, or increase the number of cars they own without having to move to a house with more parking. In the long run, if there’s a shortfall of parking, surface lots can be redeveloped into parking buildings if the demand really exists. On the other hand, an over-provision of parking means leftover vacant sites that can be redeveloped, or acquired by the local council for public open space (something Japanese cities could do much more of, though).

A less obvious consequence is how we see the effects of “overspill” parking, where the demand for parking is greater than what is provided on-site. Conventional approaches to parking see overspill parking as a negative consequence to be avoided if possible. Under the market model, however, overspill ceases to be seen as a problem at all, and simply business as usual. Overspill parking is catered for by other commercial parking providers in the area. For the public in general, there’s no negative effect, since there’s no free on-street parking spaces to compete for. For the commercial parking operators, the overspill parking is actually a money-making opportunity.

Parking also covers its costs. Market pricing for parking spaces means that a carpark brings in income greater than any alternative use of the site - since if it doesn’t, the use can simply be changed. Parking then can be an asset, not a burden.

Lastly, the market model frees the government from needing9 to decide on the “best” amount of parking. “Prices do the planning”, as Donald Shoup advocates: the private sector is entrusted to add and remove parking, at its own expense, as needed, without central planning.

The bad

The proof-of-parking system is probably the best-known part of the Japanese model amongst people interested in parking policy. Conceptually, it is definitely important: ensuring that car owners themselves are held responsible for parking. But the bureaucratic system itself is costly to administer, time-consuming to comply with, and is probably unnecessary. For starters, it only applies to overnight parking, not the parking that comes from actually using the car for its intended purpose - to drive it to somewhere other than your own house.

But even at home, there’s issues. Without enforcing the on-street parking ban, there’s too much temptation to defraud or corrupt the proof-of-parking system. And if on-street parking enforcement is regular enough to remove the temptation to cheat, the proof-of-parking system becomes superfluous.

Japan’s parking minimums, such that exist, are also unnecessary. Smaller developments (typically under a threshold of around 1500m² - 2000m²) are exempt, but numerical standards still apply for larger developments. Countries like New Zealand with a more discretionary urban planning system may still want to conduct traffic analyses for large-scale developments, even if they abolish parking minimums in favour of the market approach generally. But this can be case-by-case, and can give credit for developments that can expect to get a significant fraction of their visitors by walking, cycling, or public transport. A strict numerical standard is unnecessary.

Japan also allows vacant lots to be quickly turned into carparks, which means that in a real estate downturn, parking supply can quickly flood the market and drive down prices, undercutting more capital-intensive but land-efficient parking buildings. This discourages investments in more efficient parking being made in the first place, in turn encouraging ugly and wasteful surface parking. This flood will also increase traffic. It also means that vacant land is typically only ever used for parking, even if it would only be lightly used, and makes land-banking more viable.

Lastly, Japan’s policy towards on-street parking is mostly not to have any. Zero tolerance makes sense in a place with uniformly narrow streets, but the exceptions are generally not thought through: they’re simply a money-making way of using spare space, not used for any public goals. It also makes loading and unloading goods far more complicated.

The consequences

Japan’s system of market parking exists, in general, across the whole country. In major metro areas with dense development and excellent public transport, the result is that cars are far less common than they would be in other cities of the same size, even cities that also have high-quality public transport. Cars don’t impose a significant cost on non-drivers, either, with the costs of cars generally placed on car owners themselves.

But the system also holds up in suburban or rural areas that are more car-dependent (albeit still less car-dependent than suburban or rural areas are in the Anglophone New World). Big-box retailers in suburban areas often provide free parking for customers, and most rural and suburban houses have off-street parking. But public commercial parking lots still provide all the visitor parking that small villages and towns need, without needing either on-street or on-site parking. Market parking still works, even where driving is the only practical option.

Applying the Japanese model overseas

Some large retailers provide ample free parking and promote it as a feature. While many large retailers support parking minimums, they are still free to provide free customer parking without them, which is also common in countries without minimums. Photo: author, CC-BY-SA.

Some large retailers provide ample free parking and promote it as a feature. While many large retailers support parking minimums, they are still free to provide free customer parking without them, which is also common in countries without minimums. Photo: author, CC-BY-SA.

Some parts of the Japanese model are directly and immediately applicable overseas. Other parts are probably not worth copying, such as the proof-of-parking system. But other parts need some adaptation.

Countries like New Zealand also have significant existing stocks of on-street parking with no alternative use, particularly in residential areas. A market model would need to incorporate these spaces. One obvious possibility is “Shoupian” dynamic pricing - installing parking meters, and charging whatever price keeps occupancy at about 85%. Pricing could also simply be set at a market-clearing level comparable with whatever price private operators in the area are charging. (Those two schemes would likely result in very similar prices in places with large parking demand).

Other options include residential permit schemes, time limits, reservations for particular uses like loading spaces, or allocating on-street spaces to particular premises. Many slower-growing or declining areas probably also have so much existing on-street parking that it can simply be left unmanaged, while providing all of a neighbourhood’s parking needs.

New Zealand has a strong tradition of access to places like remote beaches, reserves, forest parks, and national parks being free, including parking. This is entirely possible to preserve: parking is a very local demand, so there’s no inconsistency between paid parking in towns and cities, and having government-provided free parking at particular destinations.

Lastly, a market model still has room for subsidies or discounts. We may be concerned about the elderly or people with disabilities having access at an affordable price: it’s possible to offer vouchers or reimbursement specifically to the needy, without subsidising parking for the general public.

In a nutshell

- In Japan, making sure that there is adequate parking is chiefly seen as a responsibility of the individual owner of the car, not property developers, businesses, or the government.

- Thanks to an urban form that makes walking easier, and strong competition from rail and subways, cars are seen by many city dwellers as a leisure item, rather than a necessity.

- In rural areas, cars are still a necessity, but the market model still provides both on-site and shared parking.

- Since there is little or no on-street parking, and illegal parking is relatively heavily policed, there is no such thing as an “overspill” of street parking.

- “Prices do the planning”.

If you’re interested in reading more about the Japanese system, I highly recommend the single most valuable resource I used in writing this piece: Paul Barter’s report on parking policy in Asia for the Asian Development Bank. I’ve also listed other useful references below.

References

Asian Development Bank. (2011). Parking Policy in Asian Cities. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28935/parking-policy-asia.pdf

Japan Statistics Bureau. (2007). Japan Statistical Yearbook. Tokyo: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication.

Kanagawa Prefectural Police. (date unknown). Application procedure for a vehicle parking place (garage) certificate. Retrieved from https://www.police.pref.kanagawa.jp/eng/e_mes/engf4001.htm

Seidensticker, E. (2010). Tokyo from Edo to Showa 1867-1989: the emergence of the World’s Greatest City. Tokyo: Tuttle.

Shoup, D. (2005). The High Cost of Free Parking. Chicago: American Planning Association.

Sorensen, A. (2004). The Making of Urban Japan: Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty First Century. London: Routledge.

Sorensen, A., Okata, J., & Fujii, S. (2009). Urban Renaissance as Intensification: Building Regulation and the Rescaling of Place Governance in Tokyo’s High-rise Manshon Boom. Urban Studies, 47(3), 556–583. doi:10.1177/0042098009349775

Reinventing Parking. (2014). Japan’s proof-of-parking rule has an essential twin policy. Retrieved from https://www.reinventingparking.org/2014/06/japans-proof-of-parking-rule-has.html

Notes

-

Then called “Edo”. ↩

-

But not for all the time between: the Pacific Theatre of World War II was motivated in huge part by Japan’s desire to gain access to oil fields in South-East Asia that were then controlled by Britain and the Netherlands, in modern-day Indonesia, Malaysia, and Myanmar/Burma. However, this desire for oil was motivated by oil’s many possible military uses, not for civilians. Japan’s military success in the area also did not last long. ↩

-

Literally, “down-town”, although without many of the connotations of “downtown” in English. “Down” is literal: they were usually low-lying, which in turn was because they were near ports and canals. The implication is a poor area, which was normally synonymous with being reasonably central, having narrow streets, lots of home industries, and cheek-by-jowl living. The opposite is yamanote, “foothills”, the large estates of the samurai and nobility further from the sea and common people, and therefore at a higher elevation. ↩

-

In theory, the tolls are to be removed once the system is paid for. However, tolls are pooled across the entire expressway network, so all expressways will have tolls until all expressways are paid off. It’s extremely unlikely that this will ever happen: pork-barrel politics mean that lots of remote rural sections of expressway were built at great expense but don’t see nearly enough traffic to pay for themselves. These will need cross-subsidy from the tolls on busier sections for the foreseeable future. ↩

-

This was unusual but not unique in the West. France also opted for a generally-tolled motorway network, and in New York Robert Moses used the cash cow of tolls on bridges and tunnels to build himself a road-building empire. ↩

-

The United Kingdom briefly included, but in the 1970s abandoned minimums again and now has a parking policy similar to continental European countries, based around limiting parking in central cities. ↩

-

Tokyo is apparently fairly typical of Japanese cities, including much smaller cities. Parking minimums for commercial premises in suburban Tokyo are around 1 space per 300sqm of floor area, nearly ten times lower than rates in Sydney or Auckland which are around 1 per 30-45sqm. ↩

-

Some English-language sources say 1962, instead. ↩

-

Local governments could also choose to also adopt restrictive parking policies to limit the amount of parking as well, although in Japan they generally do not. But it’s entirely compatible. Restricting parking is something Auckland and Wellington already do in their city centres. ↩